Global sea levels have been steadily rising for millennia, but this process has been accelerated over the last century due to global warming, global ice volume, ocean heating, and other processes. It is a controversial subject that’s difficult to predict, and different regions will be affected by rising sea levels and storms at different degrees based on their local climate and geology.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that global sea levels will rise around 20-70 cm before the end of the 21st century, but many argue that these figures are far too conservative and that observed sea level rise over the last few decades has already exceeded the best case projections. Coupled with changes in storm patterns due to climate change, countries all over the world are preparing themselves for defence from the sea. Our featured project on the International Levee Handbook and Community of Practice highlights current international best practice in levee security.

For centuries, the Netherlands has relied on its natural sand dunes and human-made dykes, dams and floodgates to defend itself against the sea. Roughly one third of The Netherlands is famously located below sea level, including 60% of the country’s 17 million people.

The contours of the country have been drastically altered over the last 1000 years by storm surges. A series of storm surges in the 12th century resulted in Lake Almere becoming connected to the North Sea, forming the Zuiderzee, and public works in the 20th century returned the Zuiderzee to a fresh water lake.

In 1916, the Zuiderzee flooded and destroyed much of the arable land surrounding the area. The reaction to this flood marked a turning point in Dutch flood control. Before the 1916 flood, most flood control measures were small scale, locally organised and managed through water boards. In order to prevent further large scale agricultural disasters, the decision was made to build a massive 32 km long dyke 90 m wide across the Zuiderzee to break it from the North Sea -- the Zuiderzee Works. The last hole of the dyke was closed in 1932, and cars and bikes were moving across the dyke as early as 1933. Since then, a second 27 km long dyke has been built across the fresh water lake, and a new province has been reclaimed from the lake where almost 400,000 people currently live.

In 1953, disaster struck again when a storm surge hit the west coast of the Netherlands, raising the sea level 5.6 metres. The surge resulted in extensive flooding and killed over 1800 people, mostly in the southwestern provinces. Another ambitious plan was drawn up to protect the southwestern corner of the country from the sea. The Delta Works consisted of dams, sluices, locks, dikes, levees, and storm surge barriers that link peninsulas stretching into the sea, shortening the exposed coastline. These works were completed from the 1960s through until 1988.

The large-scale public works of the Zuiderzee and Delta have proven very effective against flooding and storm surges since their construction in the 20th century. In the 21st century, The Netherlands has concentrated on smaller scaled projects, and Waterfronts NL has been at the centre of two innovations to protect the coastline and reinforce existing dykes from the advances of the sea: one man-made solution, and one built on natural processes.

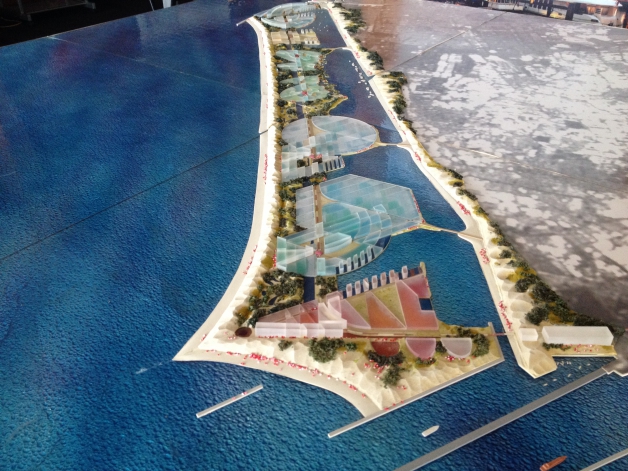

In 1994, Waterfronts NL founding members KuiperCompagnons and Royal HaskoningDHV joined forces to perform a feasibility study for a new solution to protecting vulnerable coastlines. The “Dutch Delta Concept” was a revolutionary idea that has now been applied internationally. The concept takes an existing fragile coastline and proposes to develop new man-made islands in front of it, creating a sheltered bay. The man-made islands can be developed with sediment from the bay, doubling as a sea defence enclosure and as new land for potential development. The Netherlands Water Partnership is currently working with South Korea, Vietnam, Columbia, Mozambique and other countries worldwide to apply this water defence model, and our featured project this season in Jakarta, Indonesia further explores this concept in action.

A second approach was developed in the 2000s when Waterfronts NL participants Grontmij and Royal HaskoningDHV were involved in the planning and feasibility of the “Delfland Sand Engine”.

A large part of the Dutch coast is protected by natural sand dunes. These dunes can be heavily eroded by storms, after which recovery takes place under calm conditions. The Dutch government carries out regular sand nourishments along the Dutch coast to maintain the required safety level and provide sufficient protection against flooding. In the future, the required nourishment volumes will most likely increase significantly due to sea level rise.

To anticipate the increased future sand nourishment requirement, the Dutch National Innovation Platform suggested creating a Sand Engine along the Dutch west coast. A Sand Engine is a large-scale sand nourishment (creating islands or flats along the coast), providing a sand buffer which will be distributed by natural processes over time. The creation of one large sand buffer decreases the yearly required nourishment demand and offers opportunities for the development of nature and recreational functions.

This project, executed in 2011, put 21 million cubic metres of sand rising up to 7 m above mean sea level off the coast of the Netherlands, where it is currently being re-distributed by natural occurring winds and currents, reinforcing the coastline and revitalising natural habitats. The project cost a fraction of what the normal process of reinforcing dunes in the Netherlands would cost, and the full results of the project are constantly being monitored to learn more about future applications. Our featured project on The Hague’s water sports zoning illustrates how the Delfland Sand Engine has reinforced natural habitats, and created new hot spots for water activities such as swimming, surfing, wind surfing and kite surfing.